Acutis and Frassati: Top of the Class? No, Saints in Life. Advice for Today’s Teachers

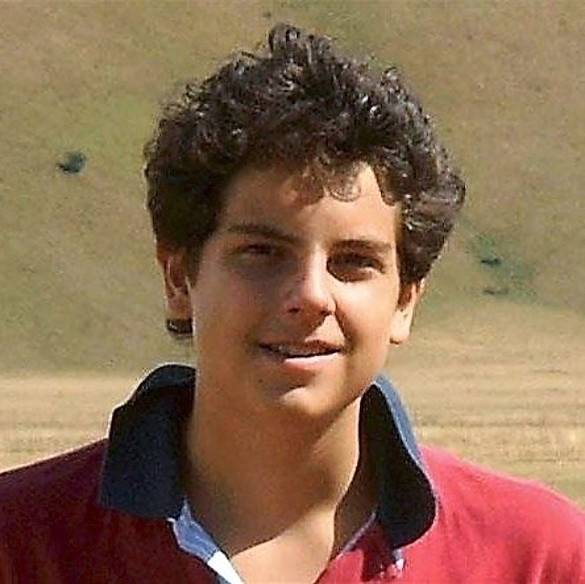

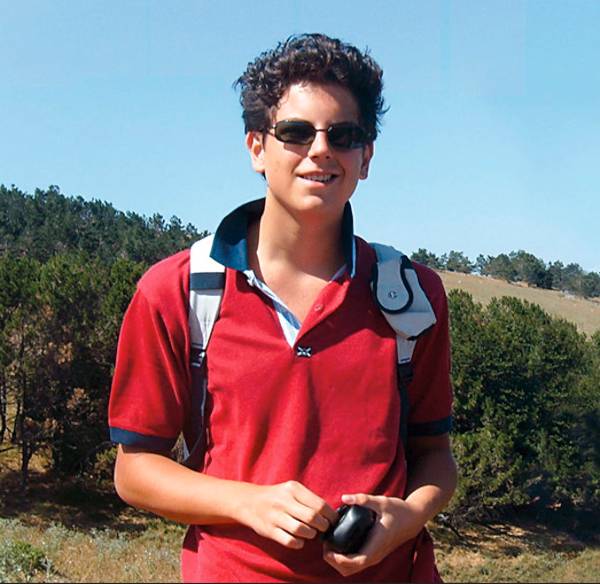

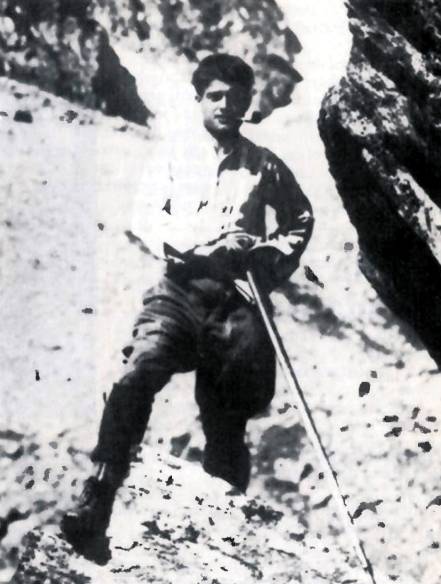

Young, good-looking, well-off, athletic, able to inspire and bring people together, passionate, seekers of truth, attentive to the least among them. Pier Giorgio and Carlo share many things in common. Both attended Jesuit schools, in Turin and Milan. While interviewing teachers who knew them or studied their testimony in depth, some common traits emerged along with insights for renewing education today.

by Laura Galimberti

“Other Things to Do”

They weren’t exactly bookworms. The two young men had plenty of “other things to do.” Documents and teachers confirm this. It sometimes happened that Carlo, though a bright student, didn’t complete his math homework because of unspecified commitments. At the Leone XIII Institute in Milan, during his fourth year in college, his math teacher, Maria Capello, recalls: “He wasn’t particularly passionate about my subject,” she says. “Sometimes he arrived late. The year ended with a slight failing grade. I gave a 5 to a saint! Only later did I find out what those ‘commitments’ really were. He was doing good deeds, without saying anything, without ever boasting about it. By September, he had recovered brilliantly, but I never even had the chance to tell him.” This is confirmed by Antonio Bertolotti, his Italian teacher in 2005: “A normal boy, pretty average. The humanities were where he felt most at home. I had no idea of what he was doing outside school hours. His passing was a shocking event. From there, we began to piece everything together.”

Frassati: after failing in Latin twice at the Massimo d’Azeglio Classical High School, he entered the Istituto Sociale. He accepted his failure and moved on. ‘The letter Piergiorgio wrote to his father is beautiful: his desire to improve himself, to move forward,’ says Antonello Famà, a long-time religion teacher at the school. This would become one of his mottos: ‘live, don’t just exist.’

Searching in depth

“Questions, questions — and that smile of his. A curiosity that was always positive,” recalls Fabrizio Zaggia, Carlo’s religion teacher in his fourth year of college.

“‘Go back to your seat! We need to start the lesson,’ I would sometimes tell him — though, more often than not, I was the one who ended up changing the lesson based on his questions.” Bertolotti, now the principal of the lower secondary school at Leone XIII, agrees: “By the fifteenth question, I’d send him back to his desk. His questions ranged from topics we covered in class to current events. He seemed genuinely interested in what I thought, and he wanted to share his own interests with me. I especially remember his handwriting — incredibly small. He was very creative when it came to writing essays: five or six pages long. Sometimes I’d get frustrated correcting them. His writing was that of a mature person; there was nothing childish about it.” When the period ended and the math teacher came in, he would then turn his questions to her: “I remember thinking he was too young for questions like that. He would often stop to pray in the school chapel. We later learned he did the same thing at his parish.”

Frassati joined the Social Institute in 1913 and met several people who would prove extremely valuable to his journey: he became interested in the spiritual exercises, which he would experience many times at Villa Santa Croce. He would pray and receive holy communion daily. He had an active faith, embodied in history and charity.

Young people for others

“Three, two, one: Menga enters in the group!” It’s a line from the short film directed by Carlo and created together with his class, at the suggestion of their religion teacher, to participate in a competition promoting volunteer work. “They rejected the video of a saint,” the teacher says with a smile. We didn’t win, but Carlo was able to get everyone involved in that project. I remember how helpful he was: “Don’t worry: I’ll shoot it, edit it, and choose the music,” he told me. He even included Morricone’s Mission, I remember. He was careful that no one was excluded, especially the introverts and the weaker ones. He was everyone’s friend. He was decisive in his ideas, but never angry or bossy.” “He was calm,” adds Bertolotti, “and someone you could trust. His classmates, in particular, enjoyed talking to him and confiding in him.”

Many friends often went hiking in the mountains with Piergiorgio. With some of them, he founded the “Compagnia dei Tipi Loschi” (Company of the Shady Characters), which, amid jokes and high spirits, aspired to deep and authentic relationships based on prayer and faith. “Joy of living and depth in relationships are qualities that coexist perfectly in them,” Famà highlights, describing them as natural builders of relationships.

Attention to the Least

Both step out of their comfort zones in which they were born. Privileges? They are meant to be used to help the least fortunate. At the Social Institute, Pier Giorgio encounters the Society of St. Vincent de Paul. “He enters the homes of the poor in 1920s Turin. He smells the stench. He doesn’t hold his nose but embraces those situations. It’s not about the aesthetics of charity, but about sharing, about concrete attention to the peripheries that Pope Francis has spoken of,” explains Famà. “His passion for study comes later, at the Polytechnic. He chooses mining engineering because he wants to work alongside miners, to improve their living conditions.”

“He gave help to whoever he met,” Professor Capello recounts about Carlo. “He reached out to others, never looking back. He gave whatever he could: a sleeping bag, a blanket to the poor. To those who didn’t need anything, he offered his smile. He gave his life to others.” “The canonization process? It wasn’t welcomed positively by his classmates,” Bertolotti confesses, “especially by the most brilliant ones. Holiness stirs up a bit of unease, especially when it belongs to the classmate sitting right next to you.”

Advice for Today’s Teachers

These testimonies challenge parents, teachers, and educators when faced with the many young people they encounter — unique, special, each one a potential saint.

Observe, Listen

“There are things that matter to young people even more than homework and studying. We must learn to listen. They have precious messages that we may not understand right away,” explains Capello. “Starting from those messages, we can then find ways to spark interests and curiosity, helping each one to grow and mature.”

“Behind every young person there is a mystery. The Lord is at work, even if we don’t see it,” adds Zaggia.

Put the Student at the Center, to Promote his magis

“Today’s young people often experience learning in a passive way — they’re lying down, so to speak. Their approach to technology is like that of a collector,” Bertolotti highlights. “It requires no real effort. The copy-and-paste philosophy is similar to that of a Neanderthal man. They are not curious, because they are neither at the centre of the learning process nor do they feel like they are. Instead, they are lost in a vast mare magnum, convinced that all they need to do is to extend a hand to obtain what they need.

Another setback is in communication: they don’t know how to formulate their thoughts or express them. There’s no logical sequence, not even in their WhatsApp messages. “Artificial intelligence will solve the problem anyway!” they think. Carlo was not one of those lying down. He did so much more. He lifted the lid off the world before him. To young people, I say: don’t waste your time — even your school time!”

“We need to help young people regain this desire to know and discover,” adds Famà. “By recognizing the young person as the subject of the educational process — and of our reflection as teachers — we can support them in moments of difficulty, appreciating and fostering their uniqueness. The magis of Ignatian pedagogy is not a theoretical concept but a relative one,” Famà highlights. “Each person has his own magis. Today’s idea of excellence, on the other hand, is a proposal that excludes. God has an individual, unique, and distinct plan for each of us, one that leaves no one out.”

An Experiential Approach to Teaching

“It is important to encourage initiatives in different contexts. Allowing young people to have real experiences helps them better understand themselves and others, and it also helps us grow together with them,” explains Capello. “There are many active projects in Jesuit schools: volunteering and walking journeys aim to nurture relationships and teach students to see the world with new eyes.”

At the Service of Others

“From the kindness box to the food chain, to collections for various charitable initiatives — there are many tools we put into practice starting with the youngest students,” explains Professor Zaggia. “Then the students grow, and so do the opportunities, which, within the network of Jesuit schools, are structural. Experiences in Scampia, in Africa, allow them to immerse themselves in different realities, challenge themselves, freely give their time, and gain a new perspective. Abroad, these have now become part of the curriculum.”

Attention to Vulnerability

“We still need to learn to recognize and embrace vulnerability, as Piergiorgio and Carlo did. Not only from a charitable perspective but also in terms of political action,” adds Famà. “Creating opportunities, engaging in dialogue, and promoting social justice.”

From the Classroom to St. Peter’s Square, teachers on Sunday will be there, next to the altar, ready to relearn from two “bright students” the art of living fully.

—

There are 937 Jesuit schools in 76 countries around the world, educating over 880,000 students. Find out more about the Jesuit Global Network of Schools.